Backstories and Backyards: Timber-r-r!

Crosscut saws turned out to be critical to the development of Floyd County during the 19th century, supplying logs to the 46 water-powered sawmills listed by name and location in the 1888-89 "Chataigne’s Virginia Gazetteer and Business Directory."

Harless Wood recalls a time when he partnered on a two-man crosscut saw to fell trees: "There was timber back then too. Big trees. We was always cutting down an oak tree. Got a six-feet saw, an ole crosscut, and we could pull it about that far. [shows about two inches wide with his fingers] Now we was all day long cutting that tree down; that was best we could do."

By Kathleen Ingoldsby

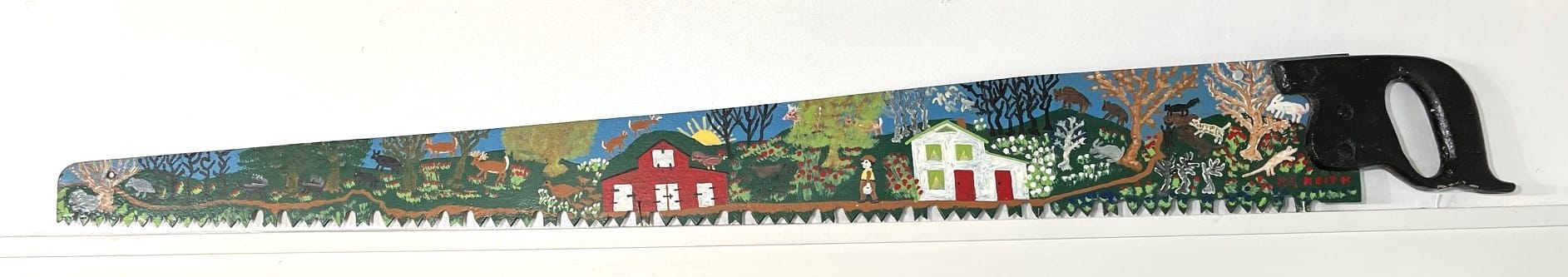

A decorative piece of folk art in the Old Church Gallery's collections introduces a topic with a very long history in Floyd County and an even lengthier history in the world. The object is a crosscut saw, long past its prime, but given a new life by Selma Keith with his imaginative scenes and painted flourishes. This one-man saw might have accompanied a two-man crosscut saw to the woods, done a full day's work, and kept the farm family both warm and protected.

As a tool, the hand saw spans the length of human history. It dates from prehistory and neolithic times, fashioned from stone such as flint or obsidian. Modern saw blades evolved after the discovery of metallurgy, first from copper, then bronze, and finally bright iron and steel.

The old school building converted into three floors of almost all types of fabrics available, and craft supplies! Plus - an extra building of upholstery fabrics and supplies!

220 N. Locust St., Floyd VA

(540) 745-4561

sfabrics@swva.net

However, one type of saw has clearly proved its worth over time: the crosscut saw, known to the Romans but coming into extensive use in Europe during the 1400s and in the United States by mid-1600s. Its wide use was made possible by a more efficient "M" tooth pattern that emerged from the original uniform, pointed-cutter pattern.

Crosscut saws turned out to be critical to the development of Floyd County during the 19th century, supplying logs to the 46 water-powered sawmills listed by name and location in the 1888-89 "Chataigne’s Virginia Gazetteer and Business Directory." Timbers cut from massive trees became beams and posts in bridges, barns, mills, homes, and braced-frame buildings, as well as providing material to Floyd's two dozen, 1880s wagon- and coachmakers. A Lomax collection 1939 folksong highlights the constant flow of logs to the sawmill:

"Come to the sawmill, sawmill, sawmill / Come to the sawmill all the day long."

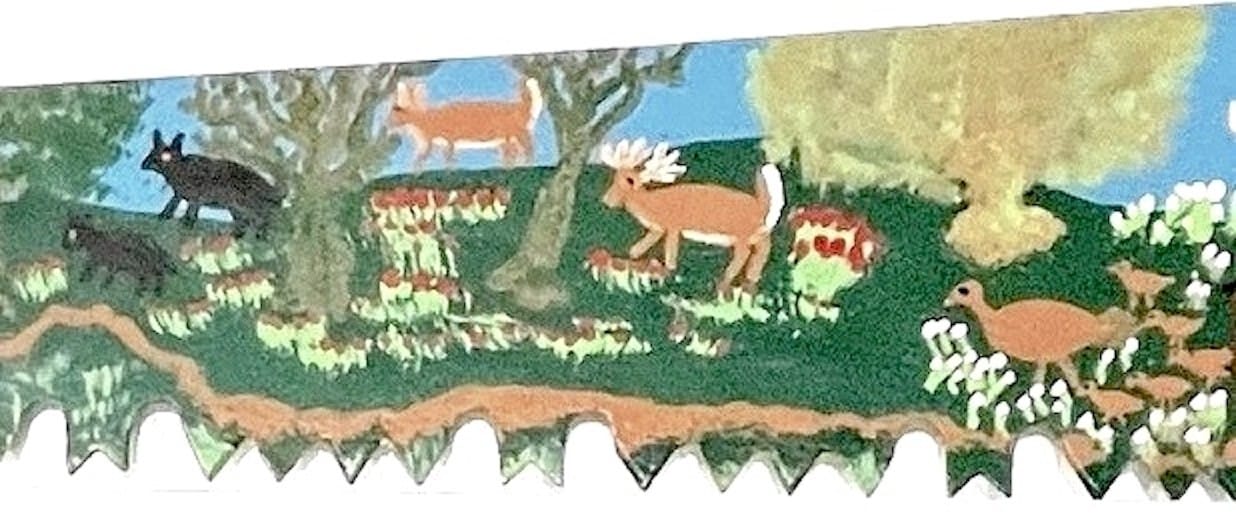

Nathaniel Selma Keith (1913-1999) painted this delightful 48-inch, one-man crosscut saw blade with scenes of farm life and collections of bear, deer, skunks, turkeys, rabbits, and other wildlife. But by the time that these storied 20th-century country landscapes came to life, the crosscut saw would have faded from popular use in the forest and on the farm.

As a hand saw, the crosscut saw runs on muscle power instead of gas, batteries, or electricity. The most important distinction from other saws is in the way the teeth are grouped, in clusters instead of being uniformly spaced as found in most woodworking saws. Shown here, the four lance-tooth cutter sections and single rake-tooth sections create a varied pattern that pulls the sawdust out of the cut. This style is designed for cutting wood across the tougher wood grain, is self-cleaning, and, when pulled back and forth, cuts in both directions — truly a handy device.

Andrew Blevins

210 N Locust Street

Floyd, VA 24091-2105

(540) 745-2777

Next to School House Fabrics on Route 8 in the Town of Floyd.

In early Floyd County, the longer two-man crosscut saw, four to ten feet long, was first used for buck-cutting or sectioning axe-felled trees. Then, after late 19th-century manufacturers began promoting "friction-less" technological improvements and the addition of rake teeth, sawyers began using the two-man saw to fell large trees.

And large trees there were!

In an interview, Harless Wood (1916-2016) underscores the number of large trees in Floyd County before WWII and during the Depression years.

"I was telling you about working in the sawmill. I cut a lot of timber that way, with an ole crosscut. There was timber back then too. Big trees. We was always cutting down an oak tree. Got a six-feet saw, and we could pull it about that far. [shows about two inches wide with his fingers] Now we was all day long cutting that tree down; that was best we could do. The bigger saw that you had, it mattered. But that was the truth. And the only way we got it sawed; we didn't have nothing but horses, and we would drag the logs in with them, and go to the sawmill and it'll be worth something."

— Harless Wood (Floyd Story Center, Old Church Gallery)

Local sawmills, both early water-powered and later electrified, have been an essential component of Floyd County life. "The Water-Powered Mills of Floyd County, Virginia," by Frank Webb and Ricky Cox, chronicles a full inventory of mills and mill life here.

The authors note that "a substantial number of pre-1900 grain mills were built at sites where sawmills were already at work," and that in an 1881 inventory, "among 16 Floyd County grain mills . . . 10 also had sawmills." Several early, water-powered sawmills are pictured in the book.

Sawmills not only provided lumber, firewood, and timbers, but were also a source of employment for many.

In his 1999 interview with David Rotenizer, Dellas Bolt relates his work with a crosscut saw during the Depression, "Hoover's time."

David Rotenizer: "Well, what's been your occupation? What kind of work have you done?

Dellas Bolt: "Sawmill. Cut timber, stuff like that. Run a crosscut saw. Me and my brother got this timber up in here [Buffalo Mt. area]. We cut five hundred thousand [board feet] for sixty-five cent a thousand. Moved right on up, and got done on Saturday. Friday, we was right on up there and sawed another set of two hundred thousand, and we got a quarter out of it. Run on a crosscut saw. Man, I'm telling you what's the truth. I worked through Hoover's time."

— Floyd Story Center, Old Church Gallery

Once it became possible to bring a portable saw to a forested site, using early steam engines or, later, gasoline-powered motors, efficiency improved greatly. With the introduction of large circular saws to cut tree trunks into rough lumber or slabs, output increased.

As Brian Childress explains to Melinda Wagner in his 2001 interview: "Later on, oh, about the time I quit, . . . on about '51 I quit, they were doing a lot of logging with tractors and loggers and bringing them in. Same way with the chainsaw. When I was in business doing old crosscut, getting timber out of Buffalo Mountain, the other side, didn't have the power saws."

Melinda Wagner: How much was standing timber going for back then?

Brian Childress: If you could find it. Eighteen dollars a thousand. When gas was twenty cents a gallon, help was twenty-five cents a hour or fifteen. I've worked at a sawmill all day for twelve and a half cents an hour. And I was just a boy, but I got to where I was doing a man's work. And so I drew a man's pay, fifteen cents an hour [laughs]. Started at twelve and a half; I got a big raise of two and a half cents an hour.

Wagner: Okay, what years are we talking about for those prices?

Childress: Those were in the thirties. Forties, it picked up a little. In the fifties, it picked up a little more. But it's been in the recent years, the last decade, lumber's been out of reason. They pay more on the stump, they pay more on the standing timber than we can get – well, when you pay a hundred dollars a thousand [board foot: 1" x 1" x 12"], it's standing. You know, you're paying for it; you got to get it cut, then logged, then sawed and haul to market; you got a lot of money before you even get there.

Wagner: Did you take it out with horses or vehicles?

Childress: Usually horses.

— Floyd Story Center, Old Church Gallery

In the continuum of logging in Floyd County, Jason Rutledge of Healing Harvest Forest Foundation recounts the changes to modern logging practice to Jason Burgard: "Now we have centralized sawmills and you basically got to haul 30 or 40 miles to sell a load of logs now. When you used to process that lumber right on the spot, right in the woods, and then haul the lumber directly to the secondary processing, which would be kiln drying and then dressing and then manufacturing furniture."

Jason Rutledge: [About the lumber industry in Floyd] "So I’ve seen that grow from — a stick mill — moved on a wagon or a truck and a couple of horses skidding through it. It used to be, that’s the way our timber was harvested. They would take a mill and set it up in the woods. You would skid the logs to the mill, saw the lumber out of them, load it on a truck, and haul the lumber to a furniture factory, and sell your lumber, green wet wood, off of the truck. And they would pay you cash for it on the spot.

"And then about ’75, they closed all those little small places – used to be a huge market for lumber that doesn’t exist anymore. It used to, tremendously, when I was young, and that’s where people used to sell their lumber to. But that’s all gone now. Now to sell lumber you have to sell it through a broker, who will take your lumber and pay you in sixty days for what they got from you..."

— Floyd Story Center, Old Church Gallery

In the 2020 interview, Rutledge relates his great respect for our forests and notes the appearance of invasive insects as a threat to a valued resource: "This Appalachian forest is the greatest forest in the temperate world. We have more diversity of species here than anywhere in the temperate world."

And so, it appears that Mr. Keith's folk art transformation of a crosscut saw not only displays a lively picture of country life, but also presents its history as an essential part of Floyd County's industrial evolution. History holds many stories, and the cultural memory embodied in a simple saw blade has the potential to parallel world history as well as the many changes in Floyd County forestry and methods of lumber manufacture.

"Backstories and Backyards" column looks back into the stories behind everyday objects, connecting each item with the people, places, and events of different eras in Floyd County history.

All Floyd Story Center interview excerpts and the images of Selma Keith's crosscut saw are courtesy of Old Church Gallery in Floyd.

October 2025 is National Arts and Humanities Month, encouraging individuals and organizations to engage with, support, and promote the arts and humanities. In 2025, the designation highlights the importance of culture and creativity in society.